Disclaimer: This post was moved from an old blog system

The problem

Picture this, you're writing a C++ project and you want to be able to read JSON. Seems simple enough, in other languages adding a library is as easy as running a single command in the terminal (NPM) and it gets added. Or writing a small description of the project location (Maven, Cargo, Gradle). How bad could it be in CMake...? Turns out, this is a major pain point even for experienced developers.

For most developers, creating project structures / initial setup is something that doesn't happen often enough to justify spending time finding a better solution than either: manually downloading and installing the library with a package manager, using vcpkg, installing with cmake, or the 48204 other possible ways of library integration. We need a single bullet proof method of library integration with CMake.

We need a better way

After deciding that this is a problem that needs solving, every project I did I iterated a little bit more and more on getting to my current "golden" structure. In this blog post, I'll go through the process of how I came to this (To the best of my memory, it's been a few years). And how to properly utilise modern CMake for (mostly) painless library integration and project setup.

First attempts with CMake

Starting my C++ journey, my CMake files looked like this (Seriously, this is my first ever CMake file... Don't judge too harshly please)

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.16)

project(opengl_pathtracer)

set(CMAKE_CXX_STANDARD 17)

find_package(OpenGL REQUIRED)

find_package(GLEW REQUIRED)

find_package(glfw3 3.3 REQUIRED)

include_directories(${OPENGL_INCLUDE_DIRS} ${GLEW_INCLUDE_DIRS} glfw)

add_executable(opengl_pathtracer main.cpp)

target_link_libraries(opengl_pathtracer ${OPENGL_LIBRARIES} ${GLEW_LIBRARIES} glfw)

At a glance, you might think this is fine - and you're right, now it is. But what this doesn't show is the countless hours of suffering I endured because I didn't know how to get CMake to recognise OpenGL, GLEW, or glfw. After a few projects using this structure, I had one major question - "How can I painlessly get external CMake targets into my project?".

Now, as a major newbie to C++ I had absolutely 0 idea how to go about this. Thankfully, right around this time I started work on RVPT, and with a lot of guidance my friend (at the time, mentor) Charles helped me learn a lot about both C++ and CMake.

The major takeaways I got was, CMake is not like NPM, it's not like Gradle, it's unique. It's its own language, and has to be treated as such. From this, the first lesson was learnt

Use targets

No seriously, CMake is very powerful and targets are one of many ways of taking advantage of this power. Using targets effectively allows you to properly handle production, tests, benchmarks, and anything else you might need. This is an example of how I use them in my code.

add_library(project_lib

#... Sources

)

target_link_libraries(project_lib PUBLIC <libraries...>)

add_executable(project

source/main.cpp)

target_link_libraries(project PUBLIC project_lib)

add_executable(benchmark

benchmark/main.cpp)

target_link_libraries(benchmark PUBLIC project_lib)

add_executable(tests

tests/main.cpp)

target_link_libraries(tests PUBLIC project_lib Catch2::Catch2WithMain)

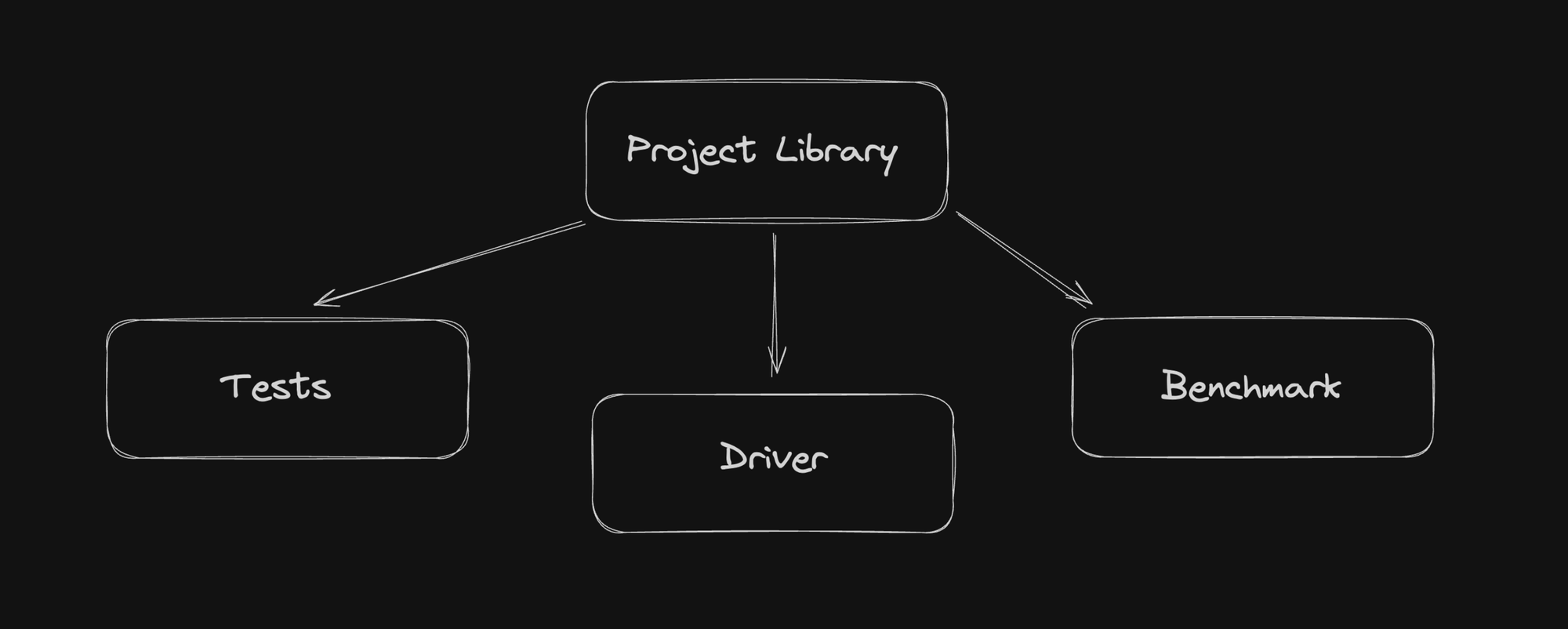

As you can see, there's a pattern. I would like to bring your attention to the fact that any given project will mostly be contained within the project_lib target, not project. This is because it allows the target structure to look like this.

This structure has helped my code structure in too many ways, but most notably. It's helped me ensure my code makes sense, before this I would constantly find myself mixing application logic to make test logic work, or adding small things here and there to optimise for a specific benchmark. Following this target structure forces you to write clean code with clear separation of concerns (I have also found that it works nicely for teams, since the driver might have a bug with how the library is used, someone can work independently with the project library for other bugs). Eventually I will write a blog post on testing and how I believe it should be done, along with another one about the differences between library code, and "driver" code.

What does this solve?

While we haven't quite "solved" the library integration problem. This gives us a very solid foundation, this structure lends itself very well for painless library integration because we're following CMake principles.

For some context, the current "ideal" project structure will look something like this

.

├── CMakeLists.txt

├── project/

│ └── <library code>

├── driver/

│ └── <code that uses project code>

├── external/

│ └── CMakeLists.txt

├── tests/

│ └── <test files>

└── benchmark/

└── <benchmark files>

For the rest of the blog post, I will be omitting the tests and benchmark (but they do still exist!).

Library Integration

Alright, here is the secret sauce to painless library integration. There are three types of libraries that exist in the C++ world.

- Header only

- Non CMake libraries

- CMake Libraries

Each of these present their own unique challenges and solutions, but all of them can be dealt with.

Header only library integration

Libraries like stb_image.h and tiny_obj_loader should be integrated by taking their header files, and putting them into a folder inside of external like so.

.

├── CMakeLists.txt

├── project/

│ └── <library code>

└── external/

├── CMakeLists.txt

├── stb/

│ └── stb_image.h

└── tinyobjloader/

└── tinyobjloader.h

We can then access them in the CMakeFile with a single line of code

target_include_directories(project_lib PUBLIC external)

This allows us to write #include <stb/stb_image.h>, and that pattern follows for any header only library (Remember to add the LICENSE file into the folder too!).

Non CMake library integration

There are libraries like ImGui, which just provide source files / header files, these are a bit more cumbersome to integrate, but nonetheless still achievable. For libraries like this, you take the source files and plop them into the same external folder like above.

Instead of using the include directly from the external folder though, we will be creating a CMake target for them. This is an example with a library I use for handling ctrl+c interrupt.

# external/CMakeLists.txt

add_library(

ctrlc

ctrl-c/ctrl-c.cpp)

We can then link to this library in our root CMake with the target name we've given it.

Keep in mind, some libraries will be more annoying, file(GLOB) is your friend here ;).

CMake Libraries

Of course, I save the best for last. If you have been blessed by the C++ gods, you'll be dealing with libraries like fmt, Catch2, glm, and many, many more... These can be added using a CMake feature known as FetchContent, which allows you to describe a target by specifying a git repo, tag, and target name. It looks like this;

# external/CMakeLists.txt

include(FetchContent)

FetchContent_Declare(

tomlplusplus

GIT_REPOSITORY https://github.com/marzer/tomlplusplus.git

GIT_TAG v3.3.0

)

FetchContent_MakeAvailable(tomlplusplus)

Some things to look out for, the name you specify in the first parameter might not be the target you need to link against. For example, with Catch2 you need to link against Catch2::Catch2WithMain. If you have issues, look through the projects CMake and find the correct target name (Though, in my experience most of the time the name you give will be the target you pass to target_link_libraries).

Finally

Well, that's it. My years of CMake experience distilled down into the shortest possible blog post, I hope that this gives you some value and saves you from dealing with the same headaches I've had to deal with to get to this point.

If you have any questions, or would like to correct me. Feel free to contact me.