Disclaimer: This post was moved from an old blog system, the original date was lost

In January of 2024 there was a challenge brought to light in the Java community, it's named 1BRC . The goal of this is to take 1 billion rows of text that look like this.

Hamburg;12.0

Bulawayo;8.9

Palembang;38.8

St. John's;15.2

Cracow;12.6

Bridgetown;26.9

Istanbul;6.2

Roseau;34.4

Conakry;31.2

Istanbul;23.0

Each line follows the format <name>;<reading>, where name is the weather station name and reading is a decimal point number with 1 digit of precision. Your goal is to ingest all of this data, and produce an output that follows the format {<name>:<min>/<mean>/<max>,<name>:<min>/<mean>/<max>}.

Originally, this challenge is intended for Java (as you can see in the repository). But since I don't want to touch write Java again even with a 10 foot pole. I decided to use a language I'm much more fond of, and use the same setup as the Java version.

Setting the challenge up

Getting the dataset

If you read the repository and go to the "running this challenge" section, you'll find that you need to do the following.$ ./mvnw clean verify

$ ./create_measurements.sh 1000000000

Knowing that testing code with the full 1 billion rows would be painfully slow for the first tests, I decided to make two files. A measurements.txt, and measurements_large.txt, with sizes 1x10^8, and 1x10^9 respectively.

Making the C++ program

As much as I would like to create a small subsection on my IDE / C++ setup across my machines, this is not the time and place. Keep looking back here every once in a while to see a link to a future blog post on my C++ development setups.

The initial "just get it working code" can be found here

How to time execution speed?

Due to doing this challenge on MacOS, I have access to time <program>. This is what I ended up using, note that all measurements here are not done strictly and averages of runs. They are simply whatever number I saw after running the program a few times. (Yes, this is not how you "should" do things, but for a small fun challenge, I think it's inconsequential)

Initial Run

Note: All time measurements will either be {Time} seconds or {Time}x seconds. If there's an x, it means that it's scaled by a factor of 10x from using the smaller dataset.

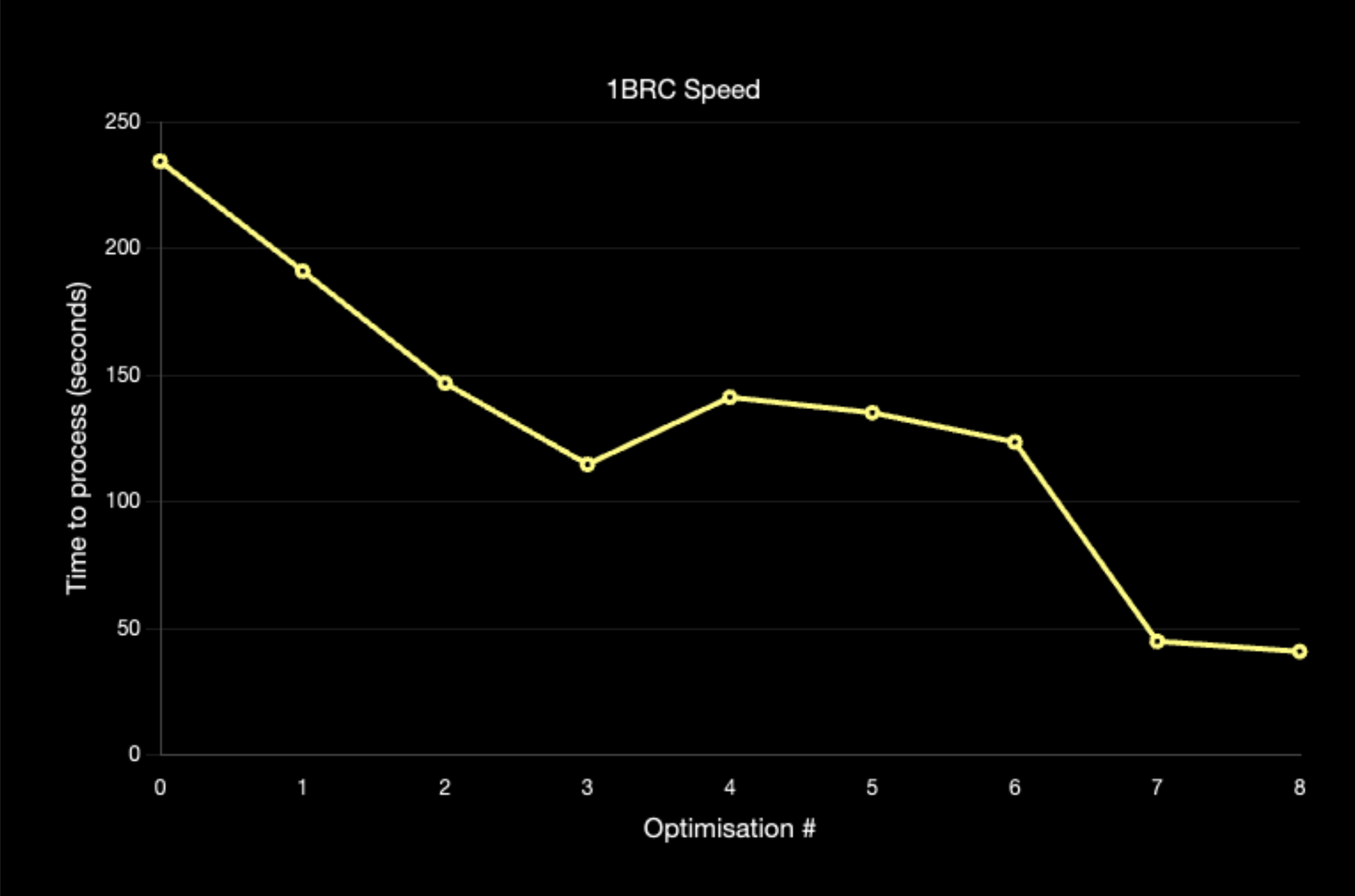

The first, completely unoptimised run clocked in at a blazingly fast... 234.3x seconds. Obviously the blazingly fast part was a joke, but it's also much better than I had expected given the lack of optimisation. In the rest of the blog post I'll go over each of the optimisations I made to get to my final time.

Optimisation 1 191.0x seconds (-43.3s)

My initial hunch of what was slow was the fact that my current flow for processing the data was as follows

- Go through file line by line and populate

std::vector<reading> - Iterate through the

std::vector<reading>and store the "final" measurements in astd::unordered_map<std::string, reading_over_time>

To solve this, I changed the flow to be - Go through file line by line, and use a single

std::map<std::string, data_entry>to keep track of the final data while processing.

Takeaway: Write code that is simple, and expressive first. If it doesn't meet performance requirements, then make it faster. Otherwise (Even if you know that it could be faster) prefer to be expressive and clean than having unneeded performance.

Optimisation 2 146.8x seconds (-44.2s)

Next up, the way I was reading files by doing

std::stringstream load_file(const std::filesystem::path &path) {

auto file = std::ifstream(path);

auto stream = std::stringstream();

stream << file.rdbuf();

return stream;

}

Is simply the result of how I typically do file reading (which returns stream.str(), to get a std::string at the end of it). I figured that since I can use std::getline on a std::ifstream as well as a std::stringstream. Creating that extra stream was a waste of resources, so I made the code

std::stringstream load_file(const std::filesystem::path &path) {

return std::ifstream(path);

}

Which was a very nice speed up.

Takeaway: Only write the code you need, justify every line of code as if you have to defend it in court. Honestly, in hindsight I didn't even need a function (Later this is changed).

Optimisation 3 114.7x seconds (-32.1s)

Since I took out most of the really low hanging fruit (to the point they were touching the ground), I figured I should go to the low hanging fruit. If we look at the hot loop

auto semicolon = size_t(line.size());

while (line[--semicolon] != ';');

const auto name = std::string(line.begin(), line.begin() + semicolon);

auto &entry = data[name];

const auto measurement = std::stof(std::string(line.begin() + semicolon + 1, line.end()));

We see that we have 2 major allocations here.

- Storing the city name

- Parsing the float with

std::stofrequires us to have astd::stringof the text.

Getting rid of the city name wasn't initially obvious to me (I wasn't aware you could use astring_viewfor the map key). So, I went with writing my own float parsing routine which was the following

float parse_float(std::string_view input) {

float result = 0.0f;

float multiplier = 0.1f;

for (char c : std::ranges::reverse_view(input)) {

if (c == '-') {

result *= -1.0f;

} else if (c != '.') {

result += static_cast<float>(c - '0') * multiplier;

multiplier *= 10.0f;

}

}

return result;

}

Takeaway: Try to minimise allocations in your hot loop, 99/100 times it's going to give you a speed up without even needing to break out a profiler.

Optimisation? 4 141.2x seconds (+26.5s)

Now hold on! Why am I including a slow down? Because while it is making the code slower, it's preparing it for multithreading and opening the door for more optimisations in the future.

So... what did I add that made it slower? I added batching, so now instead of processing line by line, I can give a function a batch of lines to process where the results can then be aggregated together

Takeaway: Just because your idea slowed your code down, doesn't mean that it won't give you potential for even more speed up.

Optimisation 5 135.1x seconds (-6.1s)

Before this optimisation, cities were printed in alphabetical order from the map's nature of ordering elements by key. While this was nice and simple, the standard libraries ordered map in C++ is typically not the fastest thing. Ultimately, we're using this map for a billion insertions - we need speed. At this point I saw 2 paths to make this faster

- Use a library's map instead (The C++ standard really limits how fast implementations can make their map).

- Use

std::unordered_map.

Ultimately, I ended up going with std::unordered_map because I didn't want to add a dependency and wanted to see how fast I could go with just my code and the standard library.

This does result in a small issue, we need to keep track of the unique city names - and have them sorted by the time we go to print. To fix this I added a std::set<std::string> that names are added to, this is then used for printing in order using the std::unordered_map to look the data up (Remember this decision, it becomes a problem later on).

Takeaway: Know your language, and common pitfalls. For C++ I suggest watching as many talks that are performance related as possible.

Optimisation 6123.5x seconds (-11.6s)

After doing some profiling I found that most of the time was still spent in the map.

![[Screenshot 2024-03-23 at 02.24.55.png]]

Since I had started work on a chess engine (blog post coming soon tm) a few months ago, one of the optimisations that were implemented involved something called perfect hashing. To boil it down, while hash maps are O(1), their constant speed can be quite slow. This is due to having to deal with collisions, a way to mitigate this if you know your data set is creating a perfect hash function. This is a hash function with the important property that, for your dataset - there will be 0 collisions. For my dataset the PHF was

[[nodiscard]] std::uint64_t name_to_index(const std::string &name) {

return (std::hash<std::string>()(name) * 336043159889533) >> 50;

}

This resulted in being able to retrieve and lookup entries very fast since all of the data was O(1), but with a much lower constant.

Optimisation 7 44.9x seconds (-78.6s)

Honestly this optimisation is quite stupid in my opinion, the next big thing the profiler was showing was that the std::set I was using for storing ordered names for iteration was now the thing that was taking up most of the time in the function. My solution was, brace yourself - this is truly a genius move.

- names.insert(name);

+ if (names.size() != 413) {

+ names.insert(name);

+ }

I know the amount of names in the dataset, and I feel like storing the names is a bit of cheating so I settled on this instead.

While I have this hardcoded, a trivial thing to implement would be using the same hash table with the names and indexing into a bool of if it's been seen or not. I believe this might actually be faster since you're just using the set for the sorting. (Then you might be able to use a different data structure that's better for this?)

Ultimately, this was the final single threaded optimisation and I was quite happy with my final time of 44.9x seconds to process 1 billion rows on a single thread.

Optimisation 8 40.88 seconds (-4.02s)

Finally, now that I was happy with my single threaded time I could take advantage of Optimisation 4, which added batching to the whole application. This was made in anticipation of multithreading, which was added in this optimisation step.

Overall, I was quite happy with my ability to process 1 billion rows in 40.88 seconds. Especially given that I was on my laptop hardware and not my PC with a much more powerful CPU.

Cool Graph

Closing thoughts

While I was proud of myself for the 40.88 second time I got, I was still nowhere near the Java leaderboard. As someone who really believes in C++'s performance, this made me very upset - I was letting the language down with my time. Ultimately, I decided to call it here for this challenge and be happy with my time. I won't be rewriting this to get even closer to the Java record of 1.5s and break the 1s barrier. Or... will I?